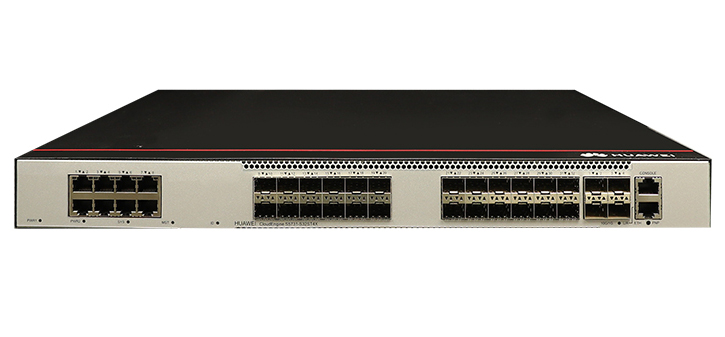

Image: Piranka via Getty Images

Image: Piranka via Getty Images Imagine listening to chirping birds and being able to pull out your phone and decipher what they're saying to each other. Then picture yourself going on a safari in Africa and following a conversation between a pair of elephants. Think that sounds farfetched? Think again: It's actually part of the tech-enabled future the Earth Species Project (ESP) wants to build.

The ESP is a nonprofit founded by Mozilla Labs cofounder, Aza Raskin, and Britt Selvitelle, a member of the Twitter founding team, and it's leading the charge towards decoding non-human communication using artificial intelligence (AI).

Also: ChatGPT's 'accomplishment engine' is beating Google's search engine, says AI ethicist

Being able to understand your cat's innermost thoughts sounds fascinating. But the benefits of understanding animals go way beyond listening into a conversation between your dog and its canine buddies when they're out on a walk.

In fact, the ability to decipher animal communication has direct implications for conservation and the protection of our planet.

Decoding animal communication could lead to the development of tools that aid in conservation research with non-invasive methods. Scientists could gain the ability to understand previously undiscovered characteristics of how animals within a species communicate, but also how they hunt, eat, develop relationships with each other, and how they see and process the world around them.

Also: Boston Dynamics robot dog can answer your questions now, thanks to ChatGPT

Does a wildcat understand what a human really is? Could an elephant's memory enable it to pass along tales from one generation to another?

Through machine learning techniques, we could gain the power to decipher collected bioacoustic data and translate it into natural human languages. This information can be applied to conservation attempts and scientific research into different animal species for wildlife population assessments.

But as noble and innovative as the task is, it isn't easy.

Much of this research will be based on large language models, much like those used to power Google Bard and ChatGPT. These generative AI tools have a strong command over human language, as they can understand and generate responses in different languages, with a variety of styles and context, thanks to machine learning.

Also: AI can write your emails, reports, and essays. But can it express your emotions? Should it?

Large language models are exposed to massive amounts of data during many stages of training. These models learn different inputs to understand the relationships and connections between words and their meanings.

Essentially, they are given vast amounts of text and data from different sources, including websites, books, studies, etc.

They're then exposed to human trainers that stage conversations with them to help the LLM continue to learn different concepts and even understand context, acquiring the knowledge of what human emotions are, how they work, and how to accurately express them through language.

This is how you can ask ChatGPT to be extra empathetic in a conversation and it will follow through. It is inherently incapable of feeling empathy, but it can mimic it.

For humans, language is a system of words and sounds that, although different in every region, enables communication between people. As AI is born from human intelligence, it's much easier to create an artificial model that can process natural language than it is to do the same for animal communication.

Also: People are turning to ChatGPT to troubleshoot their tech problems now

The biggest challenge the ESP faces in its efforts to decipher animal communication is the lack of foundational data. There is no written animal language available to train a model. What's more, the varying communication formats between species poses an additional challenge.

The ESP is gathering data from wild and captive animals around the world. Researchers are recording video and sounds and adding annotations from biologists for context. These data points are the first steps towards creating foundation models for a wide range of animal species.

The IoT is also making it easier to increase the dataset of animal communication styles. The large variety of inexpensive cameras, recording devices and biologgers means scientists can gather, prepare, and analyze data from afar. This data from myriad sources can then be pulled together and analyzed with AI tools to decipher the meaning of different behaviors and communication forms.

Also: This new technology could blow away GPT-4 and everything like it

ESP cofounder Raskin believes the kind of technology needed to create generative, novel animal vocalizations is close: "We think that, in the next 12 to 36 months, we will likely be able to do this for animal communication.

"You could imagine if we could build a synthetic whale or crow that speaks whale or crow in a way that they can't tell that they are not speaking to one of their own. The plot twist is that we may be able to engage in conversation before we understand what we are saying," Raskin told Google.

Etiquetas calientes:

Inteligencia Artificial

innovación

Etiquetas calientes:

Inteligencia Artificial

innovación