Image: Meta

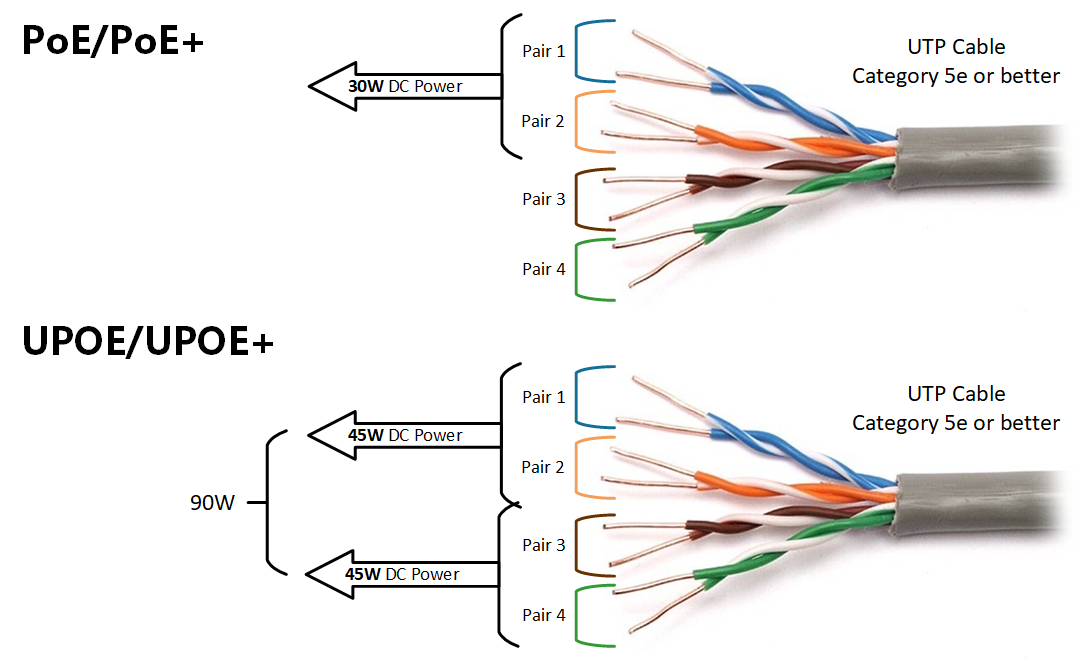

Image: Meta Meta said after being "inspired" by user feedback and privacy experts, the company has rewritten its privacy policy "to make it easier to understand".

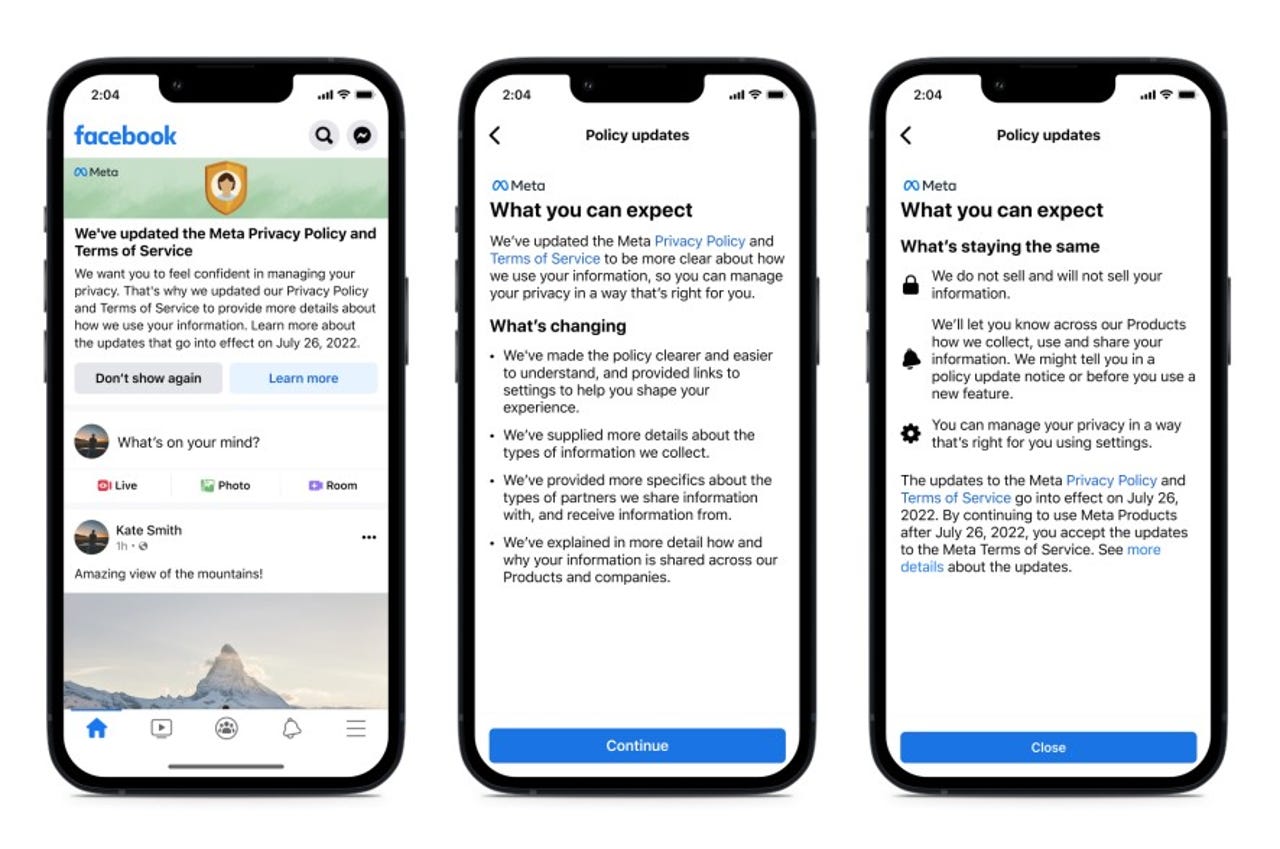

The updated policy, formerly referred to as its data policy, now provides examples of what information is collected, and how it is used, shared, retained, and transferred, including with the type of third parties. New controls to manage who can view a post and the topic users want to see ads about has also been included.

Meta has also used illustrations, a video, and a table to present the information, instead of relying on a giant wall of text.

"Our goal with this update is to be more clear about our data practices ... At Meta, we've always set out to build personalized experiences that provide value without compromising your privacy. So, it's on us to have strong protections for the data we use and be transparent about how we use it," Meta product chief privacy officer Michael Protti said in a blog post.

Protti also assured while the text might look slightly different, Meta is "not collecting, using, or sharing data in new ways .... and we still do not sell your information".

The updated privacy policy covers Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, Boomerang, Oculus, and other Meta products. It does not cover WhatsApp, Workplace, Free Basics, Messenger Kids, or the use of Quest devices without a Facebook account, which have their own privacy policies.

Alongside the privacy policy update, the company has also updated its terms of service, covering when the company may disable or terminate accounts and additional details about what happens when a content is deleted.

Meta has begun rolling out notifications on Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger alerting users about the update ahead of rule changes taking effect on July 26.

Earlier this year, Meta agreed to pay$90 million to settle a privacy lawsuit that has been ongoing since 2012.

The legal fight was caused by Facebook's use of cookies and a proprietary browser plug-in in 2010 and 2011 to track users after they had completely logged off the social network. Although users had to agree to being tracked while they were logged into Facebook, that tracking was supposed to end upon logout, according to the end-user licensing agreement, but it did not.

Around the same time, Meta also lost its appeal to have a Cambridge Analytica data lawsuit filed by the Office of Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) thrown out.

For almost two years, the lawsuit had been held up by Meta as it attempted to claim through submissions that it does not conduct business nor collect personal information in Australia, which are requirements for an entity to be sued under the country's privacy laws.

These submissions were rejected, with the Federal Court full bench labelling Meta's argument that Facebook platform merely acted as an overseas website that provides data to an Australian device when requested to do so as being "divorced from reality".

The OAIC will now look to accuse Meta of breaching the privacy of over 300,000 Australians whose data were caught up in the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which saw the data of millions of Facebook users harvested globally by consulting firm Cambridge Analytic without their consent through an app called This is Your Digital Life.

Etiquetas calientes:

negocio

Medios sociales

Etiquetas calientes:

negocio

Medios sociales